As the first Catholic pope from the United States, Pope Leo XIV has an ancestry that traces back to the Creole and free people of color from Louisiana, illustrating complex and interconnected issues of race and class in American history.

“His rise is not just a religious milestone, it’s a historical affirmation,” genealogist and former official Louisiana state archivist Alex DaPaul Lee said of the man previously known as Cardinal Robert Prevost.

When Lee first heard about the pope’s Creole roots from fellow genealogist Jamarlon Glenn, he responded, “There’s no way,” Lee said with a laugh. “But then I began going down a rabbit hole of research.”

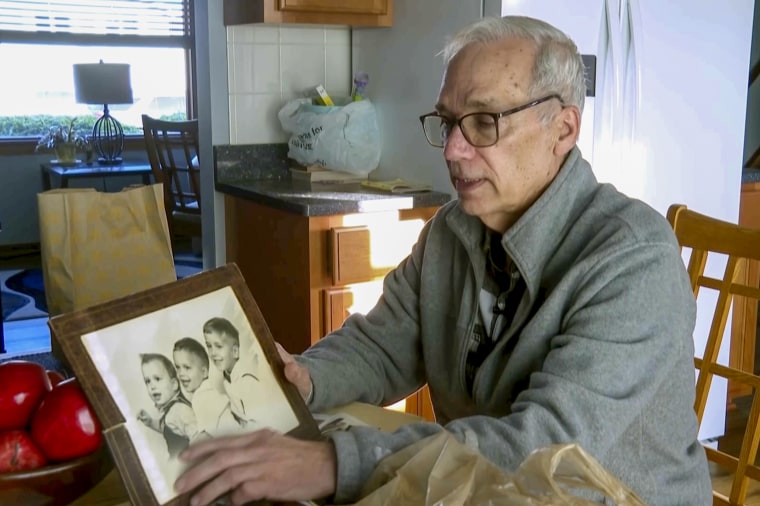

Lee, the founder of Alex Genealogy and Southwest Louisiana Genealogy Researchers, discovered troves of documents in his collection and gathered records from his network of genealogists that confirmed information about Pope Leo’s background. It also showed generations of Catholicism within Prevost’s family.

“It didn’t take long for me to realize that he was a Creole from the seventh ward of New Orleans, Louisiana, which was a prominent place for Louisiana Creoles,” he said.

The news of the pope’s Creole roots was also noted by genealogist Jari C. Honora. Leo’s brother John Prevost confirmed the connection to The New York Times and said he and his brothers had never talked about it. “It was never an issue,” John Prevost told the Times.

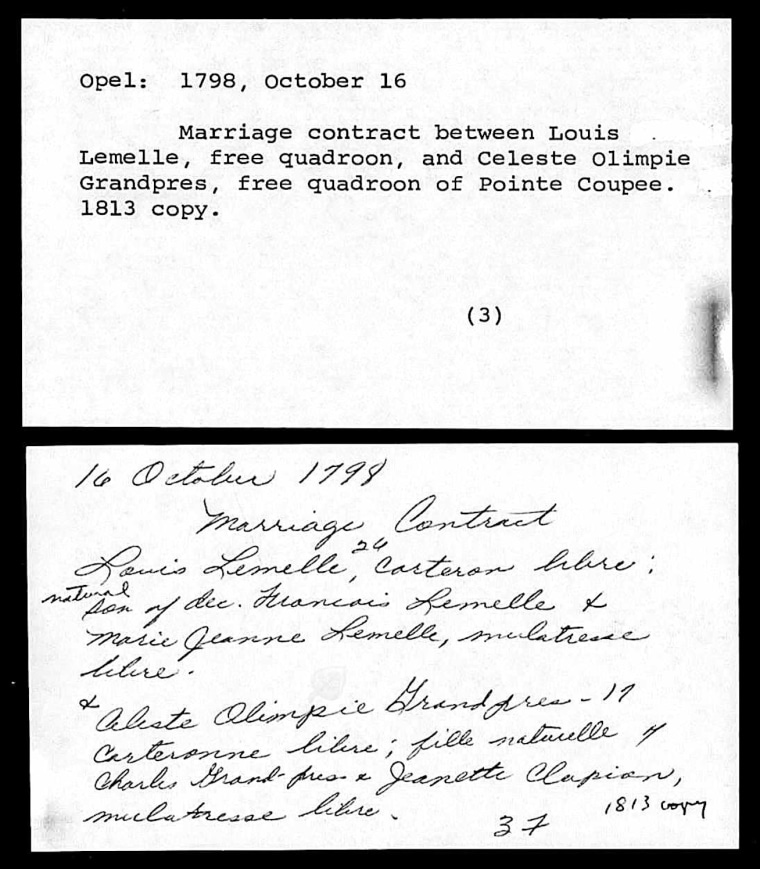

Although his paternal surname, “Prevost,” is common in Louisiana, Lee said a strong Creole connection was actually found in Pope Leo’s maternal ancestry: His great-great-grandmother Celeste Lemelle was the daughter of two free people of color, Louis Lemelle and Celeste Olimpie Grandpres. They married in Opelousas, Louisiana, in 1798, and were legally classified as “quadroons.”

“That meant they would have a fourth African ancestry or it could have been Native American ancestry,” Lee said.

The Creole community emerged in Louisiana due to the blending of cultures there. French, Native American, Spanish, German and descendants of West African countries all cohabitated in the region during the pre-colonial era when France and Spain owned the Louisiana territory.

In Louisiana during the 1700s, there were three main racial categories: the enslaved, Gens de Couleur Libres (free people of color/Creoles of color) and the white planter class, according to Lee.

The classifications within the Creole community were based on legal status and racial identity, with other categories like “mulatto” and “octoroon” often showing up within historic documents, Lee said. He added that there were also Creoles of color who owned enslaved people at the time. Documentation shows that the Lemelle family once owned enslaved people.

Lee said the Lemelle family, which traced its wealth to cattle ranching, became one of the most prominent Creole families during the Antebellum period in Louisiana.

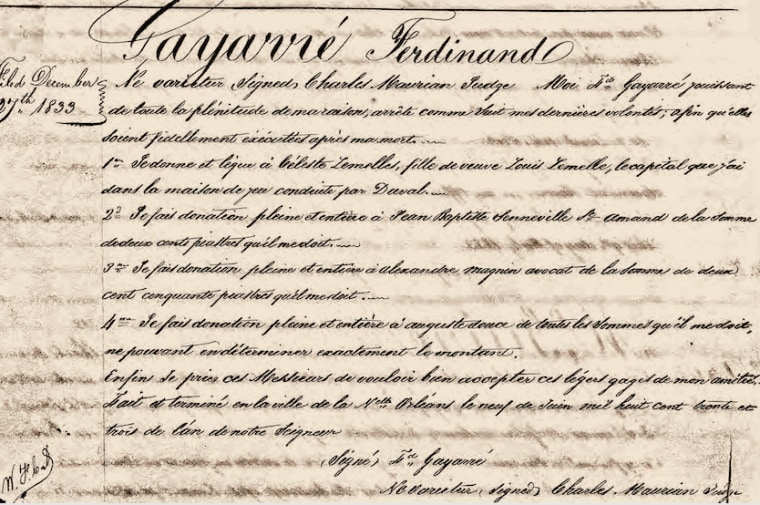

The pope’s great-great-grandmother Celeste Lemelle was a free woman of color and documents show she was given earnings from a business owned by Ferdinand Gayarré in December of 1833. In addition, she was also given land in 1850 from Frédéric Guimont, a merchant whom she had several children with. The transaction was irrevocable as a way to protect her ownership of it, Lee said.

“One of the most significant things about Louisiana was that women could own property and they have been owning property since its early inception, especially free women of color,” Lee said.

Lee pointed out where the change of racial identity can be seen within Pope Leo’s family during the 1800s.

Celeste Lemelle’s son Ferdinand David Baquie, born in New Orleans on Oct. 10, 1837, was listed as “mulatto” in the 1870 census. But in 1880, he and his entire family were listed as white.

In terms of how Pope Leo’s family ended up in Illinois, Lee said his family was likely part of the hundreds of other Louisiana Creoles who migrated north during the first wave of the Great Migration in the early 1900s.

“Illinois was once part of the Louisiana territory. They had an old post by the name of Kaskaskia where they had some of the earliest Creole people,” Lee said, adding that people of color would have had more job opportunities and better civil liberties in the northern state.

“Considering the fact that many of these families passed for white in Chicago meant they were going to have more success, regardless, because of their appearance.”

Lee said it’s notable that the pope’s racial background reflects the diverse blends of cultures that have historically merged to form the unique identity of Louisiana.

“In America, a lot of people think everything is just Black or white,” he said. “But it’s important to note that the pope’s ancestry represents a more inclusive view of what it means to be a Catholic, and what it means to be an American with Louisiana Creole ties. This is more than just genealogy, it’s a legacy.”

Leave a Reply